Visual record of Willie Mays playing baseball is frustratingly sparse. The 3,000 games, the 12,500 plate appearances, the 25,000 innings in the field—all that action on the field is limited to radio calls, highlight reels, brief clips, staged swings, home run derbies, and photographs. One of the only televised full games easily accessible on the internet was one of his last, Game One of the 1973 World Series, and an at-bat I wrote about when the Mets retired his number nearly two years ago.

Film was still prevalent enough to capture, in a limited way, his brilliance, but not the whole picture of his career. We can not search for and watch evidence of his failures, like a four-strikeout day (he did this four times in his career), nor can we study the 46 times in his career he recorded four-hits in a game. We have to be satisfied with faded reels, shaky camera angles, late zooms, poor audio. On top of that, each compilation is made up of the same swings, the same hits, the same plays in the field, the same slides into second, the same rounding of third. It’s all hat-losing speed and ferocity and power and grace: the elegant spin in his backswing, flashing his 24 as four baseballs leave the yard at County Stadium in Milwaukee, the 3,000 hit against Montreal, the reckless leap into the chain link fence and Bobby Bonds, the basket catches he’d perform for the camera before the game, and only a handful of the 7,000 plus putouts he’d make in center field.

It is something to cherish, but so much is missing.

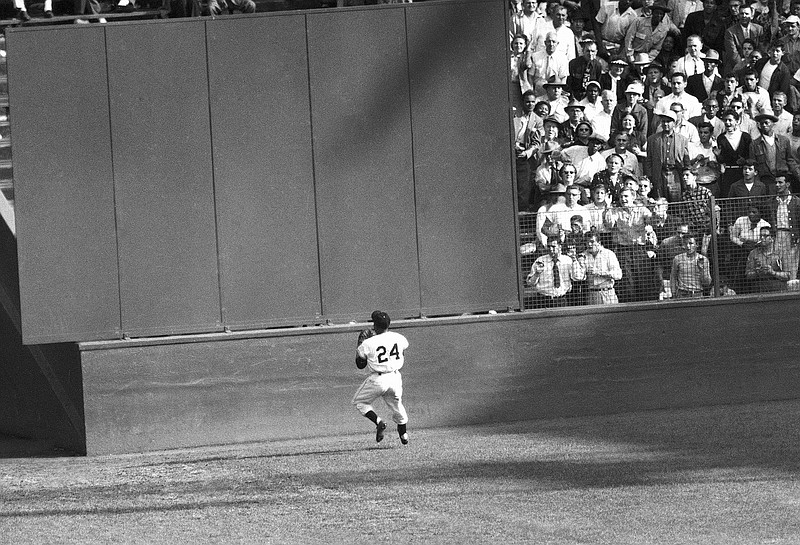

“The Catch” in Game One of the 1954 World Series is Willie Mays’s most famous defensive play, not because it’s his best, but because it was filmed.

Fans could watch and re-watch the play from beginning to end, We could hear the sound of the liner off the bat of Vic Wertz’s bat, the roar of the crowd. We could rewind, slow down, analyze Mays’s jump, his route to the ball, the way he cocked his body not to brace for the catch itself—the one that felt impossible, “an optical illusion” —but for the throw after.

The first clip I saw of Willie Mays was “The Catch” replayed on a VHS tape we owned of Major League Baseball’s greatest plays. Born nearly 40 years after the play, I could be transported through time and space from my living room in San Diego, California to Harlem, New York and watch Mays in action. It’s a complete play, a great one, but its value lies as a launch pad for imaginative extrapolation. It does the heavy lifting of being representative of all of Mays’s unbelievable and unfilmed defensive marvels.

We watch that worn clip now and pair it with Willie Mays’s high-pitched scoff overheard in conversations and interviews decades after the play, saying he made dozens of putouts like that, catches not captured by the camera’s eye but only by thousands of naked ones lucky enough to be there. And after the game, those witnesses would disperse to tell tales of what they had seen, to do their best to be film reels to their friends or family, to recount frame-by-frame exactly what they witnessed only to be frustrated by their inability to do so.

Words fail, and there is no greater disappointment for a storyteller. Even Vin Scully, a man renowned for his voice, his ability to translate the image to the ear, could not really capture the play of Willie’s that inspired him the most.

Like a list of statistical feats, we try to describe what it is using symbols and signifiers, but the greatness of Mays was never in the dissection of his game, rather in the feeling his play communicated. The joy, the wildness, the awe. What is so powerful about this meeting between two greats is not the words of Scully, but the expression on his face when he saw Willie, his tone, the fact that a 90 year old man, a legend in his own right, got giddy when his favorite ball player walked through the door.

The only time I saw Willie Mays in real life was during a San Francisco Giants pregame celebration for Orlando Cepeda’s 80th birthday back in September, 2017. Mays was in a wheelchair on the grass behind home plate, I was up the first base line about ten rows from the field with a crowd of people between us, and I couldn’t believe it. There he was. My wife took a picture of it: Willie Mays, indiscernible but there in the background, and my mug in the foreground, mouth open, eyes a little watery.

It doesn’t quite make sense for a kid like me, born nearly two decades after Mays retired, to grow up saying he was my favorite player of all time. Looking back on it now, it’s a little cringey, embarrassing, a bit braggy and annoying in the era of Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Pedro Martinez, BARRY BONDS to say my guy was the Say Hey Kid. Willie’s voice in my ear again: “Man, you never saw me play!”

In one sense, it was an attempt to connect with my family history a bit more. I grew up in southern California but my dad grew up in Salinas and my mom in Redwood City. My extended family were Giants fans. My uncle was at Willie’s first game back at Candlestick after being traded to the Mets. Forty years on, and he recounted the sound of the homer he launched leaving the bat, the eruption of the crowd, perhaps already steeped in nostalgia for Mays, as he rounded the bases. This story from the same uncle who leaned over to me at my rehearsal dinner after my father-in-law, a Dodgers fan, gave a heartfelt speech which ended with him swapping his blue LA cap for a black SF, and whispered: Classic Dodgers fan.

For many, this generational connection is the reason to follow a team and a player. It’s relational and geographic. It grounds a connection. Baseball as architecture, the roof we can all gather under. My grandpa, a San Franciscan a year older than Willie, told me stories about taking the train to Seals Stadium as a kid, going around its concrete bleachers collecting cushions to earn admission to another game. My favorite baseball memory is going to a game with him about 15 years ago. After the last out was recorded, I remember following my 80-year old grandfather as he shuffled his way out of the row of seats. I could feel his tiredness, his legs stiff from hours of sitting. We moved slowly. The crowds streamed by us. I watched his feet, worried that he might trip, as he navigated the long steps from our section back up to the walkway.

He might read this and chuckle at the preciousness of it all. He’s gotten less sentimental over the years after he had to move away from his fava beans and artichoke plants to a senior-living home closer to my parents. I texted him if he had any specific memories about Mays after the news of his passing broke Tuesday evening, and he responded with nothing in-particular, noting how he appreciated how Willie took care of his wife before she died from Alzheimer’s Disease in 2013, then wrote: “I kind of forgot Mays played for the Giants for quite a few years.” This wasn’t a totally surprising response. I had asked him a couple years back if he had any anecdotes about the DiMaggios since his family overlapped with them in the city and were both Sicilian, and he quipped: “You mean the other Italians?”

I’m a little jealous of my grandpa in this regard. He doesn’t feel he has to be too precious with these legends. Most of that is probably because he’s old, mainly deaf and has a hard time getting his phone to work. Another part, I imagine, comes with the privilege of seeing them play, of being neighbors, while Giants fans in my generation have to linger on glimpses, forced to fill in the vast gaps of the visual record the best we can. Inevitably we fail. We scan the spreadsheet of stats on Mays’s Baseball Reference page as if their window blinds, trying to peer through the numbers’ shades and see what’s behind them. What do you mean Willie played four innings of shortstop? Or recorded an assist playing third base? What does that even look like? We become desperate because we think there’s a God’s eye view that we lack, a perspective that some have and some don’t.

Arnold Hano was there when Willie Mays made “The Catch.” He wrote a book called A Day in the Bleachers describing every pitch of that game through his experience as a fan. When narrating the moment in which Mays reels in Vic Wertz’s line drive, Hano zooms-in, attempting to detail minutely all that he can take in during those seconds. The realization he comes to in this failed attempt is that a baseball play is not limited to just the physical feat itself, but encapsulates every movement by every player and coach on the field, every reaction by every fan. It is just too big, and he can not take in all that is happening. “There is no perfect whole…to a play in baseball” writes Hano. “No man can get the entire picture.”

The stained glass image of Willie Mays on MLB’s Rickwood Field t-shirts is apt. Mays’s legend is pieced together from primary sources, first-hand accounts, audio recording, newsreel, game highlights, “The Donna Reed Show” and “Bewitched” reruns, pickled memories, past-down anecdotes, backyard imaginings.

None of us have the whole image, but we got our cherished pieces. I never got to see Willie play in real life, but I saw him tap his glove before a baseball disappeared into it forty years after the fact, and that made me want to play baseball. It made me want to throw a tennis ball against the garage door with my brother, or play catch with my dad. It made me slam into the hood of a parked car outside my house trying to replicate an over-the-shoulder catch.

Willie Mays played for his team and the fans. The recent outpouring of personal anecdotes about our center fielder—The Center Fielder—reminds us that baseball, like most worthwhile things in life, is at its best when it’s relational. It’s a game, and if it’s going to last, there doesn’t need to be a recording of it, or an essay explaining its significance, or proof that it’s profitable—it just has to make us feel something, it has to make us want to share what we saw.